Life in Amish communities often fascinates outsiders with its simplicity, strong sense of community, and commitment to tradition. One practice that sometimes raises questions is shunning, a form of social discipline used to guide members back to the community’s values. Understanding Amish shunning is not just about looking at rules or punishments, but about seeing how this practice helps preserve the traditions, beliefs, and close-knit bonds that define Amish life.

Key Takeaways:

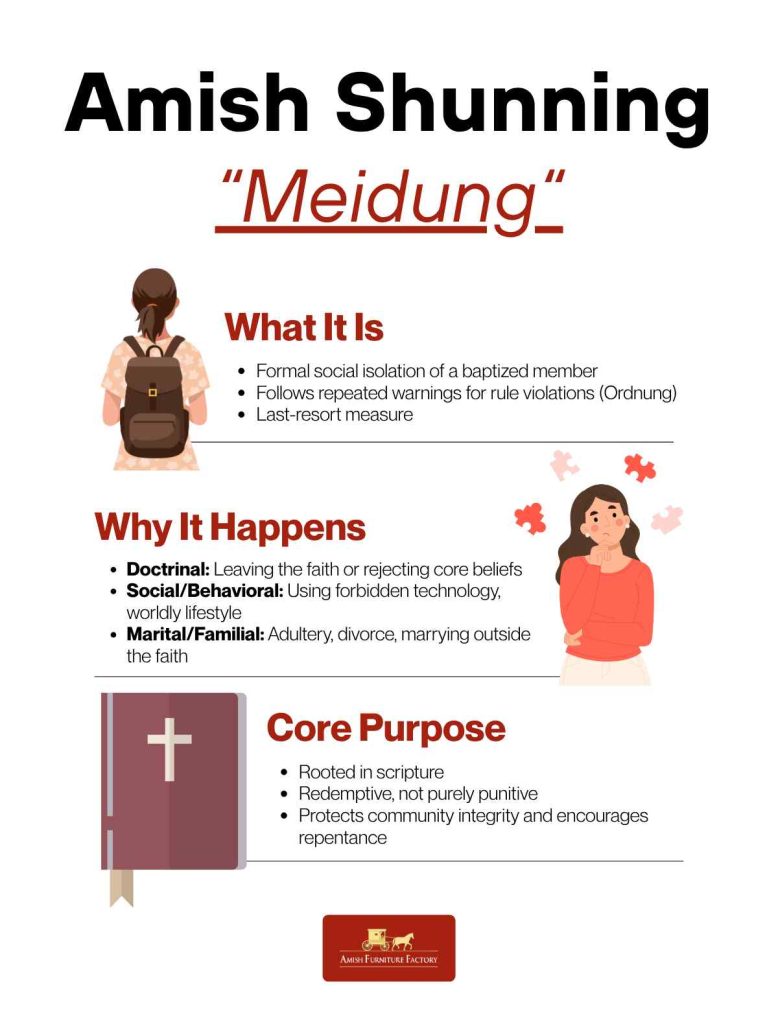

- Amish shunning, or Meidung, is a religious practice where baptized members are socially and economically avoided for violating church rules and refusing to repent.

- It helps preserve community values, humility, and cultural traditions.

- The process follows clear steps and allows for return upon repentance.

In this article, we will explore Amish shunning, why it is practiced, and how it plays a key role in preserving the values and traditions of the community.

What Is Amish Shunning?

Within the Amish tradition, shunning, or more precisely the German term Meidung, refers to a formal practice whereby a baptized member who has persistently violated the community’s norms (the Ordnung) and will not repent is socially isolated. The process begins with repeated admonitions and pastoral visits, and only as a last resort does the person enter into what is often called the “ban” (Bann), followed by Meidung: avoidance in social, economic, and church life.

The Amish themselves root Meidung in Christian scripture. For example, the apostle Paul writes:

“Do not associate with anyone who bears the name of brother if he is guilty of sexual immorality or greed, an idolater, reviler, drunkard, or swindler — not even to eat with such a one” (1 Corinthians 5:11).

In their context, the practice is seen not solely as punitive, but as a redemptive measure meant to protect the church’s integrity and prompt the individual toward reconciliation.

Why Do Amish Communities Practice Shunning?

At its heart, Amish shunning arises from the community’s collective vow to live faithfully according to the Ordnung, a moral and behavioral code that defines what it means to be Amish.

Doctrinal and Religious Reasons

The most serious offenses involve rejecting or distorting core Amish religious beliefs. A member who joins another denomination, challenges the authority of the bishop, or denies foundational doctrines such as separation from the world, risks being shunned. To the Amish, faith is a covenant with God and the church; leaving that covenant willingly is seen as spiritual betrayal.

Social and Behavioral Reasons

Shunning can also follow the adoption of forbidden technologies or lifestyles that symbolize pride or worldliness such as owning a car, using a smartphone, or dressing in modern “English” clothing. These actions are viewed as stepping away from humility (Demut) and into Hochmut (pride).

Marital, Familial, and Legal or Civil Reasons

Marriage holds deep religious meaning in Amish life. Acts such as adultery, divorce, or marrying outside the faith break not only personal vows but the sacred order of the church. In such cases, shunning serves to underscore the gravity of these choices and to encourage repentance. Additionally, although the Amish avoid lawsuits and legal entanglements, members who blatantly defy the law or draw negative attention to the community may also face shunning. “

The Shunning Process

Before a person can be shunned, they must first be baptized—because only baptized members are bound by the Ordnung and held accountable to it. In Amish life, baptism is not automatic or forced upon youth. After the Rumspringa years (a period of greater social freedom typically between ages 16 and 22), young adults must make a deliberate choice: to join the church and commit to a lifetime of obedience and humility.

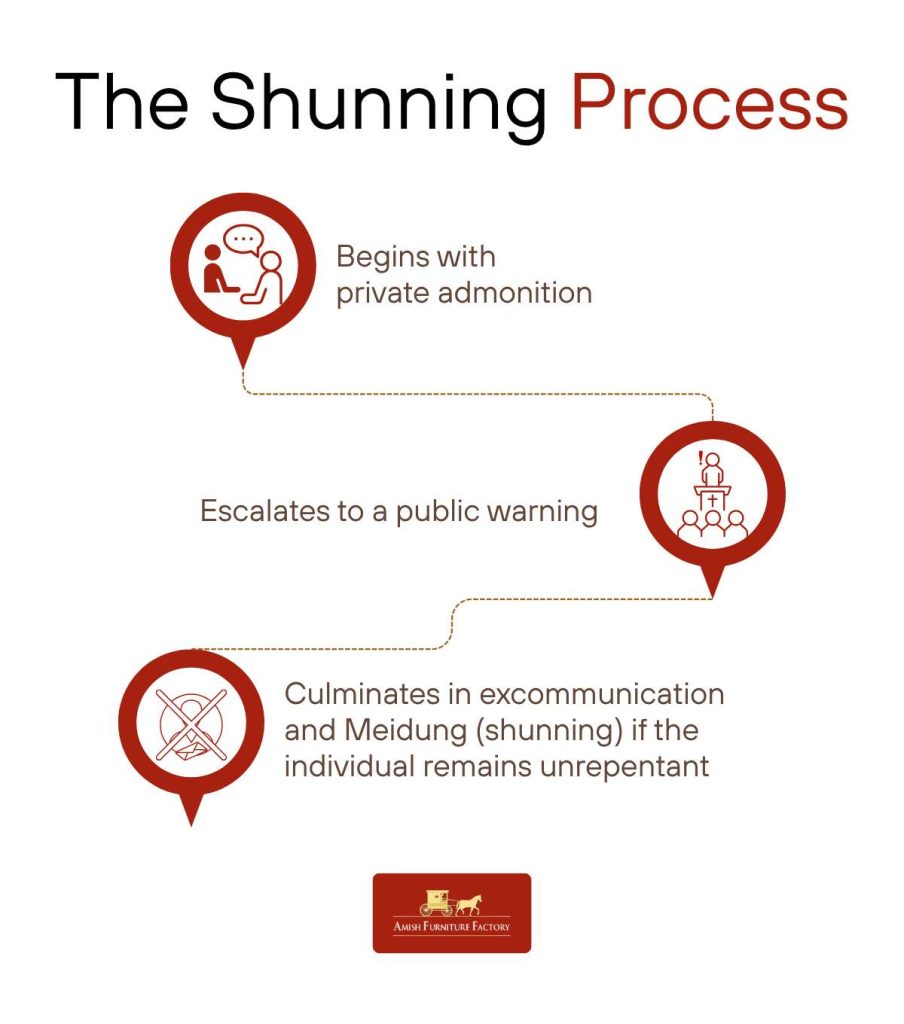

When a baptized member strays from the Ordnung, the community follows a three-step discipline process designed for correction and reconciliation rather than punishment.

Step 1: Private Admonition

The church ministers (bishops or deacons) meet privately with the individual to address the wrongdoing and encourage repentance. Many cases end here if the person acknowledges their fault.

Step 2: Public Warning/Confession

If repentance doesn’t occur, the matter is brought before the congregation. The offender is publicly warned, given an opportunity to confess, and urged once again to return to fellowship.

Step 3: Excommunication and Meidung

If the individual remains unrepentant, the church formally excommunicates them. At this point, Meidung (or shunning) begins. The congregation avoids ordinary social and economic contact with the person, symbolizing both separation from sin and hope for eventual repentance.

What does being shunned mean in the Amish community? In practice, the four main forms are:

- Religious: Barred from Communion and prayer.

- Social: Avoidance of normal interactions (visiting, talking).

- Domestic: Cannot eat meals at the same table (varies by group).

- Business: Cannot accept payment, rides, or certain forms of assistance from the shunned (varies greatly).

The Role of Shunning in Preserving Amish Tradition

At its core, what is the purpose of shunning? For the Amish, it’s about protecting a way of life rooted in humility, obedience, and faith.

Reinforcing the Ordnung and Communal Discipline

Shunning reinforces the authority of the Ordnung, the shared moral and behavioral code that governs Amish life. By upholding this standard, the community emphasizes accountability and mutual responsibility. Every member understands that obedience is not about control, but about harmony and trust within the body of believers.

Sustaining Humility (Demut) and Countering Pride (Hochmut)

In Amish teaching, humility (Demut) is seen as the foundation of Christian living, while pride (Hochmut) is the root of spiritual downfall. Shunning acts as a reminder of this delicate balance, encouraging submission to God and discouraging self-centeredness. When someone breaks from the Ordnung out of pride, shunning seeks to restore the humility necessary.

Preserving Purity, Separatism, and Community Bonds

The Amish believe their separation from the world protects them from moral and spiritual corruption. Shunning helps preserve that purity by discouraging members from embracing outside influences—whether technological, cultural, or theological.

Boundary Maintenance and Cultural Continuity

Shunning draws a visible line between what is “Amish” and what is not, maintaining the community’s cultural integrity. These boundaries serve as markers of identity, reminding each generation of who they are and why their traditions matter.

Social and Psychological Impacts of Shunning

The practice of shunning in Amish communities carries profound social and psychological impacts. On an individual level, being cut off from one’s community can feel like a form of “social death.” Those who are shunned may lose their sense of identity, belonging, and self-worth. According to one article analyzing shunning practices generally, this process can lead to “feelings of helplessness, hopelessness and worthlessness.”

Families of the shunned individual also bear a heavy burden. In many cases, the separation affects parent-child, sibling, and spousal relationships. A family unit within the community may be expected to limit contact, creating emotional fracture lines and disrupting natural support networks. For the broader community, shunning serves a disciplinary role, but it can also foster a climate of fear, conformity, and social vigilance. This can suppress personal questioning, inhibit healthy dissent, and place a heavy psychological weight on communal life itself.

Can a Shunned Person Return?

A shunned person can return to the Amish community if they sincerely repent and seek forgiveness. The goal of Meidung is never permanent exile but spiritual restoration. When the individual confesses their wrongdoing before the congregation and reaffirms their commitment to the Ordnung and the faith, the ban is lifted and fellowship is restored.

This act of reconciliation reflects the Amish understanding of grace and redemption. This also echoes the biblical principle in 2 Corinthians 2:7:

“You should rather turn to forgive and comfort him, or he may be overwhelmed by excessive sorrow.”

Through this process, forgiveness becomes not just a moral ideal but a lived expression of the community’s enduring compassion and faith.

Want to understand the complete spectrum of Amish ways beyond shunning? Explore our free guides for an in-depth look at their life and beliefs.

Conclusion: The Balance Between Faith, Discipline, and Mercy

Amish shunning stands as one of the most defining and often misunderstood practices in Amish life. While it may appear severe from an outsider’s perspective, its true purpose lies in preserving faith, humility, and community order. Rooted in scripture and centuries of tradition, it represents both accountability and compassion. This is also a disciplined reminder that faith is a lifelong covenant, not merely a belief.

Yet, at its heart, shunning is always redemptive. It aims to heal spiritual rifts, not to punish, allowing reconciliation when repentance is shown. In this balance between firmness and mercy, the Amish demonstrate a profound commitment to maintaining their way of life in a changing world.

Frequently Asked Questions

What specific actions are most likely to result in someone being shunned?

The most common reasons include joining another church, rejecting core Amish teachings, or repeatedly breaking the Ordnung despite warnings. Other causes can involve using forbidden technology (like owning a car), dressing in “English” clothing, engaging in adultery, or divorcing without repentance.

How do the Amish justify shunning immediate family members like their own children?

To the Amish, spiritual obedience must take precedence even over family ties. They believe that maintaining separation, even from loved ones who have broken their vows, is an act of faithfulness to God.

Are Amish children shunned if they leave before baptism?

No. Unbaptized Amish children are not subject to Meidung. This is because they have not yet made the adult commitment to join the church. Those who choose to leave before baptism are often treated with sadness, but not shunned. Once baptized, however, leaving the faith becomes a serious breach of vow, potentially leading to shunning.

Is Amish shunning different from excommunication?

Yes, though they are closely linked. Excommunication (Bann) formally removes a person from church membership, while shunning (Meidung) is the social and economic avoidance that follows. In practice, the two often occur together, with shunning serving as the visible expression of the excommunication’s spiritual separation.